Shooting the Moon: I, Caustic and the Labor of Revolution

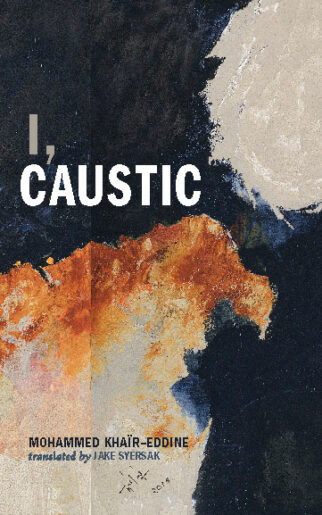

I, Caustic, the first English-language edition of Moroccan writer Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s Moi, l’aigre (Éditions du Seuil, 1970), translated by Jake Syersak, raises a mobilizing cry against colonization and state violence, weaving drama, historical narrative, and literary manifesto together to incite revolution through poetics. The work battles against political oppression during Morocco’s “Years of Lead,” a period of state violence and artistic suppression stretching through the 1960s-1980s. Amidst the rumblings of political discontent, Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine writes with an urgency to make himself heard; in I, Caustic he declares himself a writer who “was obsessed with getting it out.”

Khaïr-Eddine depicts a government wielding an almost infinite power, as luminous and as watchful as a moon that “rose to power and expected to remain there for some time.” Here, Khaïr-Eddine casts light onto the bourgeoisie and those complicit in protecting the current political order: “They never made one effort to free themselves from the moon. Just the opposite! Once in power, they arrested everyone walking around in too short of pants.” Khaïr-Eddine shows us the fantasy of joining those in power and the ways it can pull the bourgeoisie in, like a tide. As readers, we too are provoked to mock the elitism of those that “felt the need to invent a moon of their own.”

In the Postface, Khalid Lyamlahy emphasizes I, Caustic’s “two-pronged movement that testifies to the continuing relevance of Khaïr-Eddine’s writing: destruction and reconstruction, annihilation and regeneration, death and revival.” The work urgently commands its audience to join in on the labor of revolution, navigating the ebbs of darkness and the flows of reprieve.

In the form of a play, the tyrannical King threatens to clear “the city of every last remnant of liberty” and implies he could just as easily burn the neighborhood to the ground. He threatens to shut down the hospitals, condemning all the patients to their death, with images of dancing on their graves. The audience reads of the ruler’s hypocrisies: “He’ll never observe Ramadan, and yet just as soon command others to do so.” The King is, of course, backed by an extension of his tyranny, the police force, who are authorized “to spray down the square with bullets” and “to kidnap the students if they hadn’t already been condemned to death in absentia.”

A reader may find themselves wondering, “What can be done?” and then be fed motivation to rebel: “Go ahead and lash out—whenever you feel that fear may have lashed you down. And that’s just it, that’s what every last person in this world—every last person who sees nothing but the image of a police baton burnt into their memory the moment they close their eyes, a police baton about to come down on the world at any given second—should do!” Khaïr-Eddine‘s remedy is multi-generational: Where there is injustice, fight it, fight it, fight it.

In his afterword, Syersak notes that in I, Caustic “we are made aware of how much linguistic manipulation plays a role in consolidating power,” and he invites us to consider the movements of our lifetime (Climate Strikes, Marriage Equality Movement, Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, etc.) through the lens of Khaïr-Eddine‘s call to arms. In I, Caustic the narrator uses discussions about Malcom X and the Black Struggle to reject the political structures of his own environment. Syersak keeps current political movements in mind as he considers Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s writing a reminder of the necessity of working with words to gather the people of a movement. Through I, Caustic, we are shown that revolution is a vital dream and through language visionaries will find each other.

—Alysia Slocum LaFerriere

Editorial Fellow 2022-2023

Launch event for I, Caustic and Proximal Morocco (UDP) in May 2023. Details TBA.