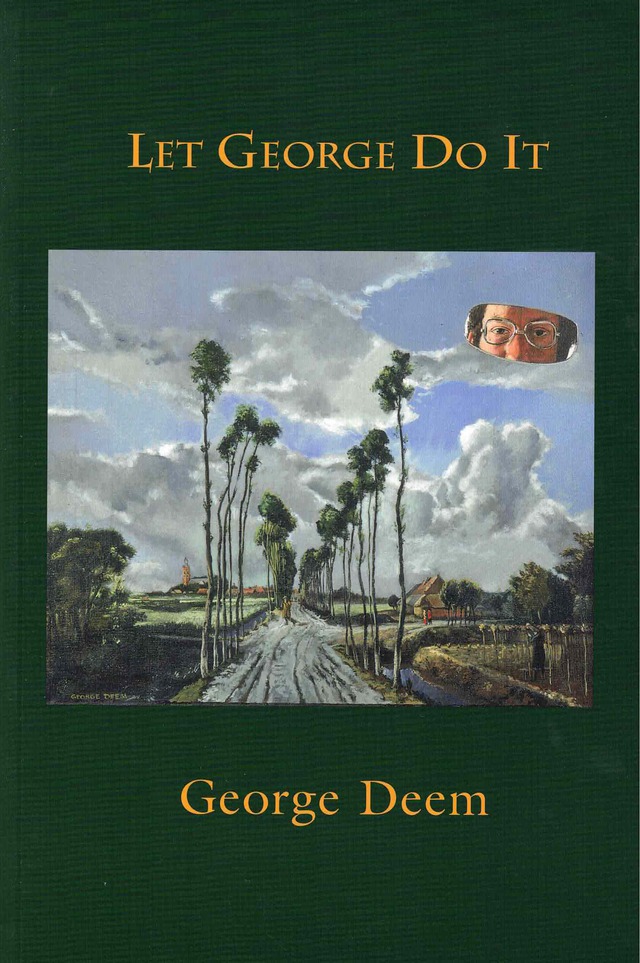

George Deem was a painter. Yet his book is not about painting. It is about writing. Although George did not consider himself a writer, from early in his life he felt the need to write down in words what he could not put into his paintings but considered important and worth keeping. He wrote what came into his mind from daily life, in various short pieces or stories, happenstance observations short and long, in sentences and paragraphs, some even in regular lines or free verse. Listening to himself, talking to himself, not to us as audience, he wrote freely, playfully, without ulterior purpose, and, whatever his subject, his language was always the language of a painter.

— from the Introduction, by Ulla Dydo

George Deem

Praise for Let George Do It

Although artist George Deem’s greatest contribution is surely his art, in which he explores the process of altering the past in a way that allows it to embrace the present and future, Deem was also insistent on the importance of language in relation to art as a process of thinking, of “thinking that is painting.” His marvelous short essays, aphorisms, and fables, accordingly, have the lightness of a pencil sketch, the delight of exploring space and color through writing and thinking itself. Placed against (or perhaps one should say beside) his drawings and paintings Let George Do It clearly reveals just how much George did through both language and art.

— Douglas Messerli

George Deem, who died in 2008, was a language artist, as well as a painter. As Ulla Dydo says in her introduction, this book “is not about painting, it is about writing.” A modest treasure. I’ve turned to it more than once, since I got it a few months back.

— Peter Quartermain, Third Factory

George Deem [was] a painter who admired master painters so much that he spent his own career repainting their works, albeit with clever alterations… Deem concentrated on making explicit references to other painters and other paintings, uncannily re-creating the style, the light, the brushstrokes, and the details of masterpieces he loved. But in addition to the overt references, there were always subtle—or not so subtle—changes… He wanted the viewer to experience not only the painting in front of him but also the referenced works that came before. The critic Charles Molesworth called the technique “temporal collage.”

— Bruce Weber, New York Times