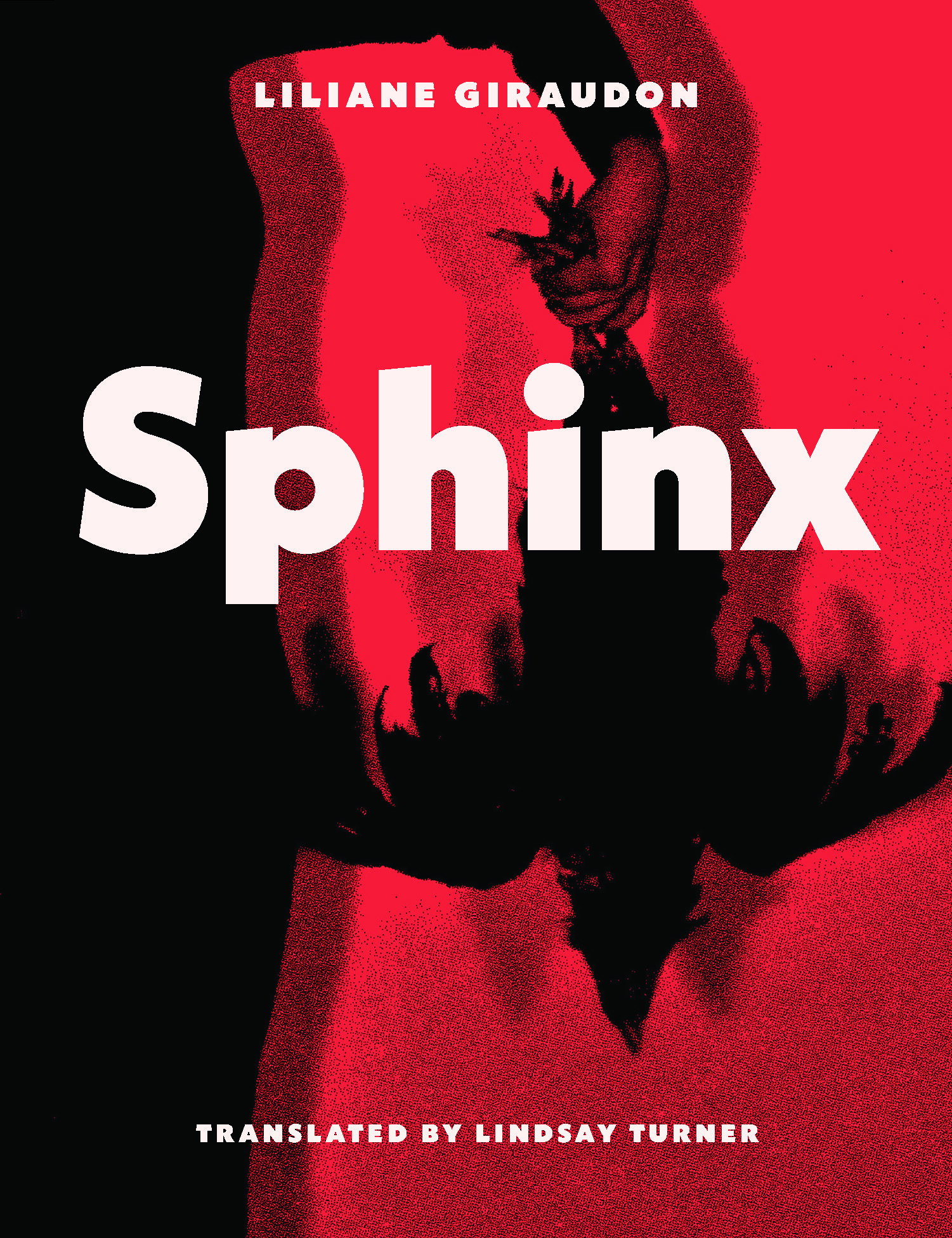

Liliane Giraudon’s Sphinx practically drips with the blood of its enemies. It’s delicately marbled, like good meat. One of experimental French writing’s most powerful and most undersung figures, Giraudon was born in Marseille in 1946. Working across prose and poetry—sometimes, too, between writing and drawing—Giraudon’s work is difficult to pin down. Enigmatic without ever being coy, Giraudon’s operational field is a mythic space, anchored in the classical past but firmly on the side of the living and our problems. “A dramatization of the present,” Giraudon writes in one of the poems, “Not History.” Lindsay Turner’s translation renders perfectly the excruciating intimacy of these hypnagogic, fabular poems.

Liliane Giraudon

Lindsay Turner

Praise for Sphinx

Liliane Giraudon’s Sphinx is a hybrid “monster” (my favourite kind of polymorph), hurtling herself off the cliff of “the fierce moment” (the tragic Greeks in tow) to enact a visceral and protean transposition: between a mythic and a present time, between the personal and the political, between languages and materialities. She (poet, translator, persona, myth) shimmies into and out of the structure of Greek tragedy, flirting with narrative and devouring raw a palimpsestic languagebeing, posing her riddles and sharpening her wit through Lindsay Turner’s deft translation. Frank and uncompromising, she demands to be heard and leaves you wanting more.

— Oana Avasilichioaei

Giradoun and Turner speak with precision and urgency, and yet we slow down to marvel at the exquisite mystery presented before us. As one of the poems posits, ghosts “exact, much more than exist.” The poems in this volume are ghosts, which is to say they imply incidents from long ago—myths—that linger unresolved in the inherited parts of our minds. She who may be the Sphinx waits; though she has shown us the way out, we long to stay, captives of her private language.

— Jae Kim

The Sphinx like the poet is “no more than a horrible singer/doing her mystery.” And the mystery always goes back to the word: “The more you look at a word closely/the more it looks at you from far off.” Giraudon writes, “A word is a form” the way that myths, narratives, burning mouths, “incessant wars,” and the names of types of cigarettes become the places where we live.

— Eléna Rivera

In this book, as in the old myth, the sphinx stands for the fragility of feminine discourse and power in the city. It’s a fragility often bathed in blood, as suggested by the omnipresent color of red in the book, about which Turner notes she “can’t think of this book in a jacket of any other color. Sphinx is a book that practically drips with the blood of its enemies.”

—Léon Pradeau, Poetry Foundation