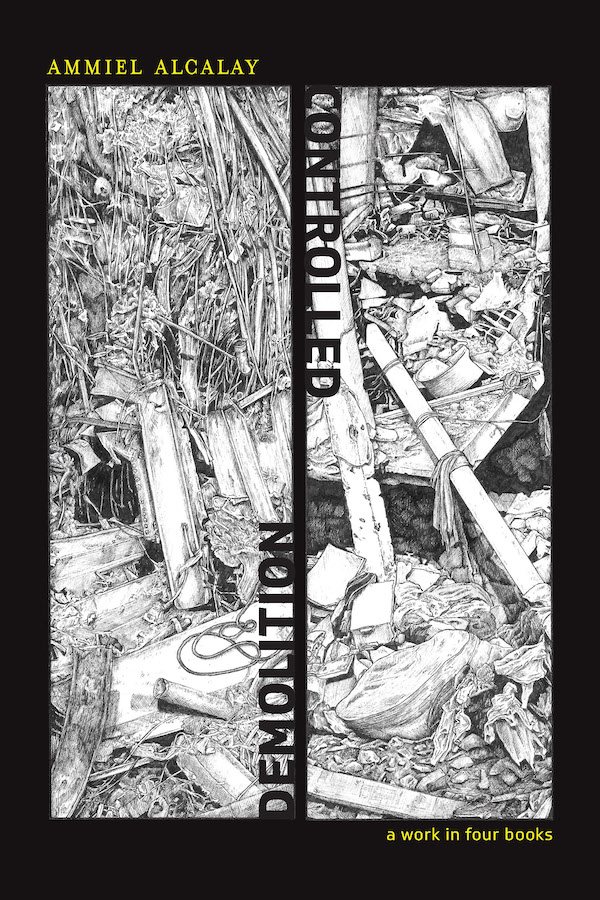

CONTROLLED DEMOLITION: a work in four books combines three of Ammiel Alcalay’s previously published poetic texts—Scrapmetal (2007), the cairo notebooks (1993), and from the warring factions (2002)—with a new work, “Controlled Demolition.” Unlike most writing categorized as “documentary” poetry, here the author and his process are constant reference points, serving as a prism to refract changes over time and circumstance in what becomes a mix of memoir, poetry, auto-critique, prose narrative, history, and investigative journalism by other means.

“The notion of follow the person is a constant in Alcalay’s poetics. The implication is this: the energy one artist can invest in really knowing the mind, commitments, affections, and beliefs of a progenitor or a kindred who is simply out of reach—too far away or too long-dead—is a conjuring agent, a potential that, once mobilized in earnest, will in some way become actual. This auto-excavation of embodied cultural and literary lineages is a through-line in Alcalay’s oeuvre, and it grounds the four books gathered in this collection, which were borne out of real-life interactions with peoples and places. The son of Sephardic Jews who immigrated from the former Yugoslavia to the US as refugees after WWII, Alcalay was influenced by his upbringing in Boston in the ‘60s and ‘70s, which immersed him in countercultural movements protesting the Vietnam War and de-facto racial segregation. He began writing in the mid-‘70s while living between Boston, Gloucester, Cape Cod, and New York City. Attending City College in Harlem, he worked in construction, auto-repair, trucking, house painting, and various other occupations, which placed him alongside a diverse array of mentors who imparted wisdom on subjects ranging from ancient languages to brick masonry to house demolition. By grounding poetry’s materials and meanings in everyday life, Alcalay re-evaluates knowledge as such, what it is and what it can be, and sets the record straight on who can access and contribute to it.” —from the Introduction

Ammiel Alcalay

Praise for CONTROLLED DEMOLITION: a work in four books

Ammiel Alcalay’s voice combines revolt and depth, and his poetics takes the reader to a new approach of literary commitment. His work goes beyond the classical concept of political commitment, in a way that makes from poetry an oasis and a source of discovering reality. Poetry and literature in the works of Alcalay are a road towards knowledge. In this sense, literature becomes a way that leads us to what lies beneath the truth. It is as the classical Arab critic al-Jurjani says: “the meaning of the meaning,” or the truth that is under/beyond reality.

— Elias Khoury

The Arabs defined poetry as “saying the unsayable” and here is a poet performing that eternal task. Alcalay distills truth and beauty in a “relentless turning of the prism.” This is a work of immense courage, “bringing back voice to the light” and posing painful questions. Pointing discursive daggers at the heart of state propaganda and controlled erasure.

In this long Qasida, Alcalay stands melancholically before the material and discursive ruins of 9/11. He traces their genealogy and aftershocks, contemplating the tectonic changes and collateral damage of past and permanent wars. Sifting through the rubble and then embarking on a journey through intersecting histories and geographies.

Poets are a tribe and in this (eternal) hour of need and darkness, the hour of late capitalism and Empire, ancestors are summoned. The words and wisdom of the elders illuminate the path and reveal coordinates. So many ghosts are guests and guides in this: Starting and ending with Virgil, of course, but there is Zuhair, Ibn `Arabi, and al-Ma`arri, as well as Pound, al-Nawwab, and Boulus, amongst others.

If the poets are Alcalay’s companions and ours on this journey, his provisions are various genres and sharp questions.

Here, too, is an elegy to the memory of all the victims of state terrorism and imperial hubris and horror everywhere, from lower Manhattan to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Palestine, always Palestine.

— Sinan Antoon

“I hear Arabia calling,” I indeed do, and I imagine a writer dictating his novel through a long-distance phone-call, and I get also the ambient sounds of a city, of a whole region, and you, the reader, receiving the voice… There is in what you hear of these cairo notebooks the cruelty of compassion, the pain of love, the tearing apart of fateful encounters. Here, a novel, a poem, are fused like the impossible couplings they portray. Poetry, history and fiction come together so that they can, further down, be broken into parts, again, anew. All that makes the tragic pulse of the Arab East is here charted on the map of a real and still ‘ideal’ city, the way it is charted on the bodies of the tortured and the dead. I think Ammiel Alcalay is possessed by love, that haunting notion that more than any other notion, drives the human mind to madness, love as it is: sacred and perverted, profaned, humiliated, and resurgent, here and there, on different places of the planet, and here and there, on the pages of this book. There is in Alcalay’s work an unabashed tenderness for the world as it is, and that makes him courageous, different.

— Etel Adnan

This book forced me to redefine my life—this is the gift of from the warring factions. It’s no one page, no single breakthrough or juxtaposition, but Ammiel Alcalay’s way of bringing the intimate and the political into the single area where neither could be identified as itself—where “it was not art but some memorial like ice” is balanced by a profound understanding: that I, that perhaps all of us, have lived our lives in a war zone—that each struggle is no more or less than any other. That if the definition of a life: a woman’s, an artist’s, a warrior’s life, is possible—it is not in counting defeat or loss but in realizing what one has managed to hold onto. To pass on. There is no aspect of ourselves, of flesh and relatedness—however hidden—that is not marked, scarred & seared by this battle, the singular battle of this time. And yet we feel. We are not estranged from what we love & beauty as reason, as Source and goal—has not been obliterated from the battlefield.

— Diane di Prima

from the warring factions is a poem (or kind of poem) I’ve been waiting to read, its disjunctures not merely replicating social and ideological fractures but having an overarching take on those fractures, showing how pieces apparently unrelated actually mirror each other, for all the differences involved… It seems to me that poetry has to do its work by “any means necessary”—and possible—and I’m tired of dogmatic assumptions about what is possible, in poetry as elsewhere. We need both narrative and disruption, revolution and continuity.

— Adrienne Rich