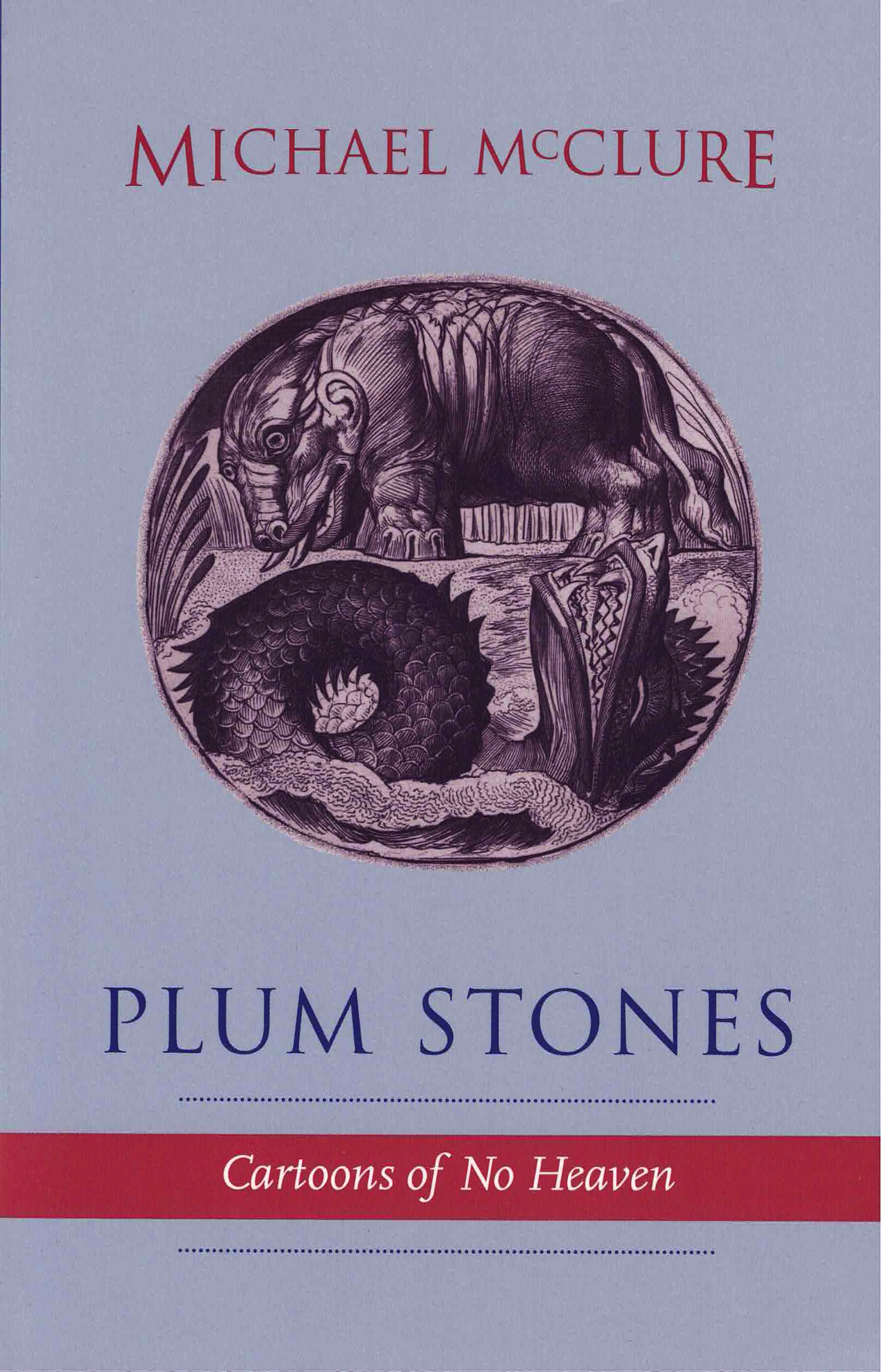

In Michael McClure’s Plum Stones/Cartoons of No Heaven, the shapes are abstractions like DNA (statement of relation and in some poems one-word centered lines on a page) which as a language can’t ever be the same as the object (such as “black lily”). Yet he breaks down a distinction between text as object and the phenomenal object of “black lilies” (words), and physical sensation (of the “speaker” or reader of those words)… He transposes (enacts) the (comic book bubble) language of his poetry as theater; it is a mode of theater in both his poetry and his plays — in both, the distinction between surface and intuitive apprehension is broken down — or between that which is “visual” and (that as) language.

Michael McClure

Praise for Plum Stones/Cartoons of No Heaven

Michael McClure shares a place with the great William Blake, with the visionary Shelly, with the passionate D.H. Lawrence…

— Robert Creeley

What appeals to me most about Michael’s poems is the fury and the imagery of them… The worlds in which I myself live… the private world of personal reactions, the biological world (animals and plants and even bacteria…), the world of the atom and molecule, the stars and the galaxies, are all there; and in between, above and below, stands man, the howling mammal, contrived out of “meat” by chance and necessity.

— Francis Crick, discoverer of the DNA double helix

At once, these poems move us into uncharted waters: The poet alone moving through time and the timeless mind, stepping slowly now, aware of the craters just beyond the hissing tongues of water, aware of the snakes and goblins, the poet alone moving through himself into the sacred and holy place of no thought — that soft and peaceful place where there is no thought and no preoccupation with the Self. No ego. No eyes. Only spirit. Ghostly peace. And simply content now to be.

— John Aiello, The Electric Review

Like much of McClure’s work, Plum Stones deliberately echoes itself, with lines from previous poems becoming the generating elements of new work–as if any single direction were essentially illusory. The poem took one form at this point, but at another point it might take another form. The rush, the speed of the verse is considerable. One does not “contemplate” these poems in the way that one might contemplate a haiku standing alone on the page. With McClure you rush through the poetry “for the sheer, ordinary, mammal / joy of it.”

— Jack Foley, Alsop Review