Features reviews, discussion questions, and writing exercises for teaching Aja Couchois Duncan’s Restless Continent and Vestigial.

Jump to: Book Descriptions · Lesson Planning · Reviews · Supplementary Materials · Contributor Bios

Restless Continent

Lush with elemental imagery, Aja Couchois Duncan’s Restless Continent communes with a North America that speaks elegiac, celebratory, and melancholic histories human and geological. In this collection, the body of that land and those histories fuses with the body of Duncan’s language, the body of memory, and the physical body. Intertwining English with Ojibwe, this debut collection of poems ominously hails and holds us in its ethereal sound, bearing sharp witness to the ruptures perpetuated by the violences of humanity—bodies and lands colonizing and colonized, naming and othering, stamping life into disappearance—while inviting us to forge with Duncan the mythologies that suffuse her poems with crystalline grace and gratitude.

Vestigial

Vestigial (from the Latin vestigium, meaning “footprint”) tracks a poetic narrative across multiple chronologies and scales—from the personal to the geologic. Following her debut collection Restless Continent (Litmus Press, 2016), Aja Couchois Duncan continues to investigate ecology and heritage as a story of entangled becoming, synchronizing movements of deep time with the transient substance of touch.

As Duncan writes:

“In Vestigial, I am exploring evolution, biomedicine, gender, lust, climate change and loneliness though characters that inhabit multiple places in time. In this way, I am seeking to thread past, present and alternative futures in an effort to understand our current circumstances and envision their likely consequences. The book plumbs multiple disciplines and wisdoms, including geology, astronomy, archeology, ancestry, plant and animal wisdom. Through this grounding of the simultaneity of experience and our multitudinous perspectives, I am attempting to create a more authentic and indigenous narrative about aki, earth, and all of her inhabitants.”

Discussion Questions

- Revisit “Emerging from the Muck” (Restless Continent Ch.1) and “Accretion” (Vestigial Ch.1). Talk about the speaker in each one: the first person voice in “Emerging” and the third person voice in “Accretion.” What forms of language do the different voices speak?

- Consider what “nature” means in these two books, and write a list of words that come to mind. Share your list.

- Duncan compiled a glossary of Ojibwe terms to include in her first book, Restless Continent, but elected not to do so with Vestigial. Read a passage from Restless Continent that contains an Ojibwe term, and then read the corresponding entry in the glossary. Now read a passage from Vestigial that uses an Ojibwe word (for example, p.17, p.20, p.23). Notice what it is like to read without a glossary. How does the reading change? What kind of meaning emerges from an undefined word in a language you don’t speak?

- From Restless Continent, p.93: “I wrote this series, this alphabet of English and Ojibwe poems, at a time I was recovering so many lost, stolen and forgotten things. I was teaching myself Ojibwe from a dictionary and, in so doing, enacted one of the many ironies of Indigenous peoples’ experience: using the cultures and systems responsible for so much of our people’s destruction as a link through which I was able to reclaim some of what had been lost.”

The “Nomenclature” chapter of Restless Continent represents Duncan’s re-imagination of the dictionary. What characteristics of a conventional dictionary does “Nomenclature” resist? What tactics does it employ in order to re-work the dictionary form? How does this chapter enlist poetics toward the recovery of “lost, stolen and forgotten things”?

- Every year 9 languages cease to be spoken. What happens if a language gets lost? How can storytelling be a form of resistance to settler colonialism? How does Duncan’s body of work enact this resistance?

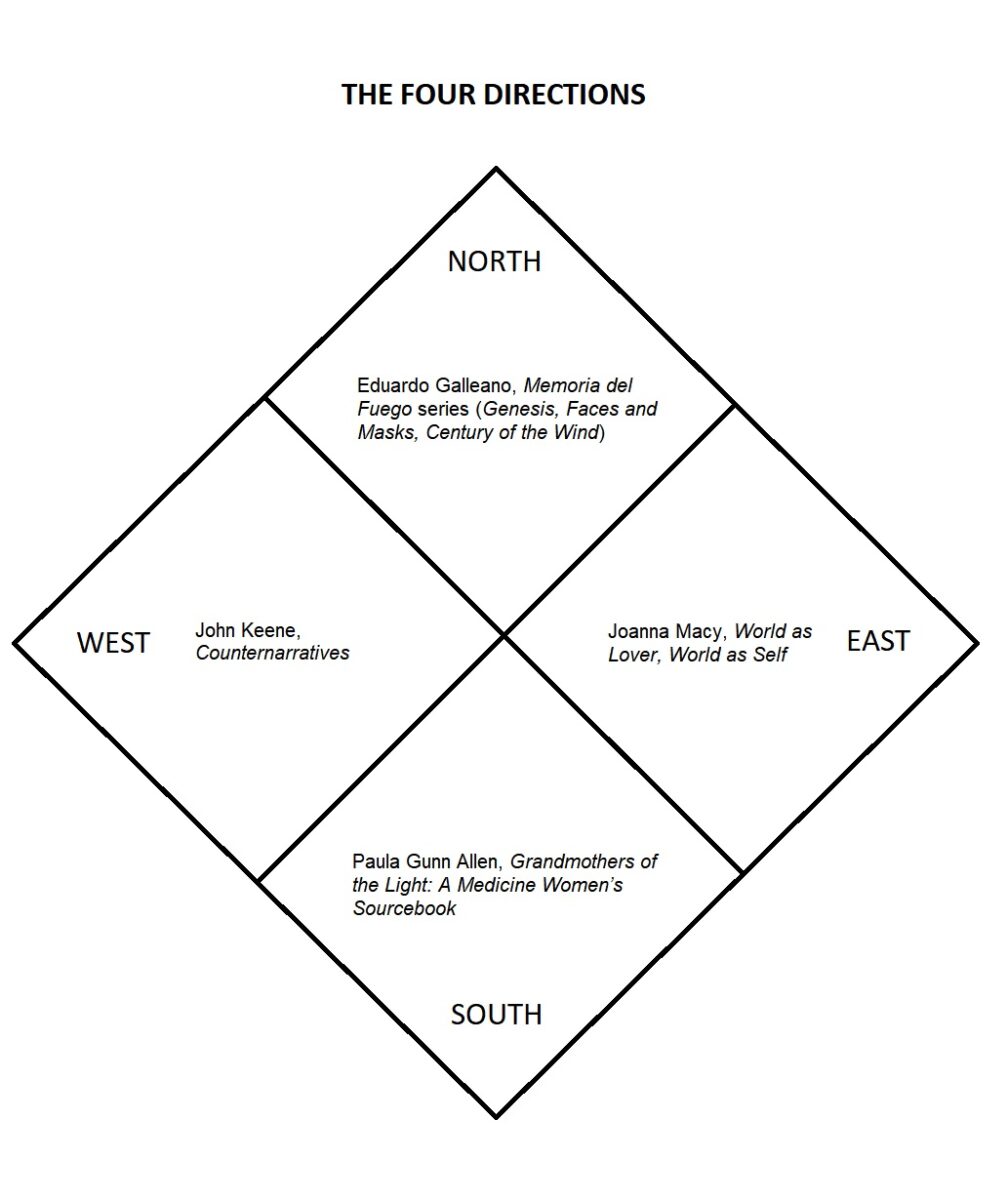

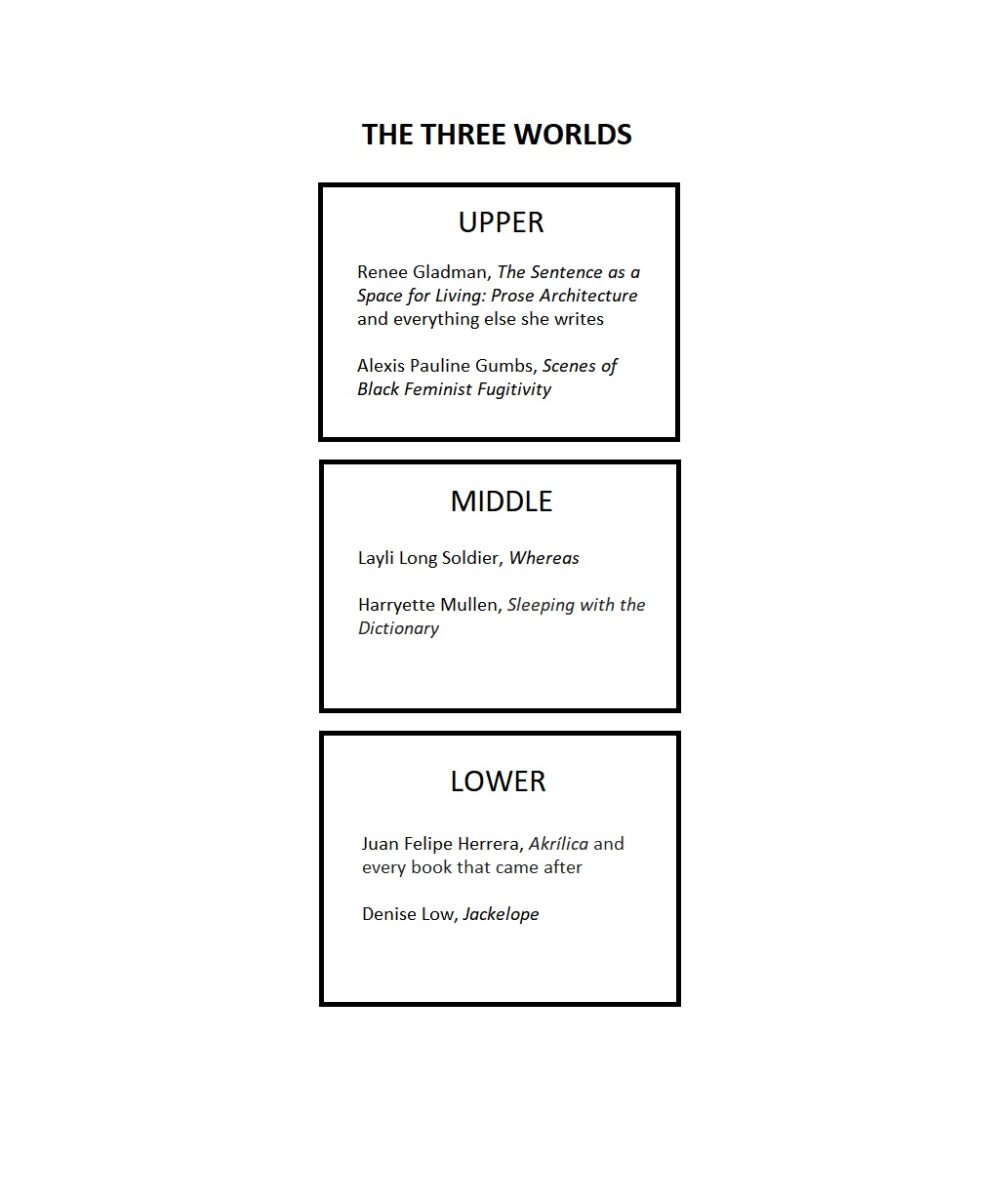

- Duncan has described Vestigial as a lyrical novel, whereas Restless Continent might fall under the umbrella of auto-ethnography. What do you understand about these genres? Come up with a list of other literary works that share elements with Duncan’s books. How might the question of genre expand/limit/challenge your reading of Vestigial and Restless Continent ?

- Duncan uses different lenses — geology, astronomy, archeology, biology, plant and animal wisdom — to view the world. What does she find fruitful in them? What does she find limiting in them? Where do they overlap? You might choose to examine the following passages as a reference:

“We have tried to codify each calamity in order to present time in equal measure from beginning to end. I have grown tired of this chronology. Reckless, I turn to the depth gauge and the shovel. Archeology requires the absence of unrecorded interventions, a world without mamigaade or theft.“ (Restless Continent, p.35)

“Convergent evolution explains many things. How different species can develop similar features. How their bodies can fit each other perfectly and yet they share neither chromosome nor tongue. How his scent is absorbed by her vomeronasal organ, signaling something to her hypothalamus that she cannot translate into words.” (Vestigial, p.7)

- Duncan’s work emphasizes processes of becoming— becoming another species, becoming another gender, becoming other. Identity is wild and open. Revisit “A New Order Of” (Restless Continent, p.52) and “Multicellular” (Vestigial, p.13). What narratives of transformation or trans-identification can you find there? How do the formal characteristics of these sections—such as the sequencing of images and interplay of voices—enhance or accommodate processes of becoming?

- Read p.60 in Vestigial and consider how climate narratives are being challenged/expanded. How is language complicit in the climate emergency? How might it be used to create/confuse responsibility? What story is told by the carbon footprint?

Related reading: “The Carbon Footprint Sham” at Mashable

- Listen to Joshua Escobar read from Bareback Nightfall. Now listen to Duncan read from Vestigial. How do these two readings speak to each other? What does Escobar’s polyvocality evoke for you ? What layers of meaning open through listening to, as opposed to reading, Vestigial and/or Bareback Nightfall?

- Aja Couchois Duncan is co-librettist of Sweet Land, an opera produced by The Industry. Due to COVID-19, the opera had to shut down early and was later turned into a film. Sweet Land blends history and mythology to retell the story of the colonization of “America” and to challenge dominant narratives of an “American identity.” Watch the film and/or read the opera’s digital program to think about the following prompts:

Both memory and history are selective processes. What does Sweet Land strive to re-collect? What does it consciously exclude?

Compare Sweet Land to Vestigial and Restless Continent. How was your experience of these works different or similar? What are some common themes? Where do they diverge? What different effects emerge from language cast as poetry on the page vs. performed as libretto?

Writing Exercises

- In a Brooklyn Rail interview with Brenda Ijima, Duncan remarks: “We abuse time in the same way we abuse so many ‘things.’ But time is not a thing. Time is a way to describe movement – of our bodies across distances, of the sun. Time is a story.” Consider how telling a story through multiple personal and planetary scales might complicate the reification of time, then:

Write a one-page prose poem that interweaves autobiography with planetary biography

or

Write a one-page 1st-person narrative prose poem that troubles the distinction between past/present/future

or

Write a one-page piece that combines the two prompts above

- Vestigiality is an “evolutionary hangover”; an organ in a living creature that no longer serves any purpose. Write down the names of 4 vestigial organs (invent some if you like) and compose a speculative prose poem for each one, exploring what it is now and what it once was.

- Write your own glossary in the vein of auto-ethnography. (Look up this term if you’re unfamiliar with it.) Use words and etymologies from any languages you know partially or fluently. Take many freedoms in your approach to the act of definition. Consider using audio, drawing, collaging, or other media in your entries. Your manner of shaping “truth” will reveal something about your own story…

Dorothy Chan reviews Restless Continent @ Woodland Pattern

Allison Conner reviews Restless Continent @ Full Stop

Brenda Ijima in conversation with Aja Couchois Duncan @ Brooklyn Rail

Micro Review by Lesley Wheeler @ Kenyon Review

Restless Continent review @ Rob McLennan’s Blog

Megan Fernandes reviews Vestigial @ Poetry Foundation

Vestigial Review @ Rob McLennan’s Blog

Related Content

Relevant News

- ‘Race against the clock’: the school fighting to save the Ojibwe language before its elders pass away @ The Guardian

- Saving a language from Extinction: Silbo-Gomero, the whistling language @ The New York Times

- Three Americans create enough carbon emissions to kill one person @ The Guardian

- Saving ozone layer has given humans a chance in climate crisis – study @ The Guardian

Aja Couchois Duncan

Aja Couchois Duncan is a social justice coach and capacity builder of Ojibwe, French and Scottish descent who lives on the ancestral and stolen land of the Coastal Miwok people. Her debut collection, Restless Continent (Litmus Press, 2016) was selected by Entropy Magazine as one of the best poetry collections of 2016 and awarded the California Book Award for Poetry in 2017. In 2020, Sweet Land—a collaborative opera project which brought together composers Raven Chacon and Du Yun, librettists Aja Couchois Duncan and Douglas Kearney, and co-directors Cannupa Hanska Luger and Yuval Sharon—was produced in the Los Angeles State Historic Park to critical acclaim. When not writing or working, Aja can be found running the west Marin hills with her Australian Cattle Dog Dublin, training with horses, or weaving small pine needle baskets. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University and a variety of other degrees and credentials to certify her as human. Great Spirit knew it all along.