Olivia C. Harrison: On Palestine Solidarity

This is the first post in a series of engagements by Litmus authors, translators, and editors reflecting on the connection of their work to the ongoing struggle and violence, current and historical, in Palestine. Rooted in our commitment to creating and maintaining space for international exchange and dialogue, Litmus Press is launching this series, War & Peace, in homage to the journal War & Peace, edited by Leslie Scalapino and Judith Goldman from 2004-2009 (preceded by enough, eds. Scalapino and Rick London, 2003, and O/Three: War, ed. Scalapino, 1993).

Unprecedented in scale, the current assault on Gaza is part of a pattern of population displacement and replacement that began a century ago and is accelerating to its logical conclusion: the total colonization of historic Palestine. As a scholar of French empire and transcolonial solidarity, my sense of devastation and dread in the face of Israel’s military response to the terrorist attacks of October 7 were matched by an uncanny feeling of recognition. In the settler colonies of Algeria, South Africa, and indeed the US where I write, non-combatants became military targets to make way for conquest and settlement. That those resisting colonial conquest and settlement through violent means were also killed does not make colonial warfare more legitimate. If we must insist on the distinction between civilians and combatants to abide by international law, we must also re-introduce the subject position of the colonized (civilians and combatants both) to understand the nature of the violence that is being unleashed on Gaza.

I was rereading Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth for the umpteenth time in preparation for my graduate seminar at the University of Southern California when October 7 set into motion Israel’s latest and to date most extreme campaign of destruction. Fanon’s analysis of “colonial warfare, which very often takes on the appearance of an authentic genocide” has stayed with me since.[1] In Algeria too, there were fierce debates about the methods and tactics of anticolonial resistance. The FLN, which deployed both guerrilla warfare and terrorist attacks targeting civilians, won the argument, and the war. The French army in turn used the threat of terrorist attacks to justify its use of extreme violence, including the torture, bombing, and mass displacement of civilians. But colonial violence came first. As Fanon reminds us, violence is the sine qua non condition of settlement. “In the colonies, the foreigner coming from elsewhere imposed himself using his cannons and his machines. . . . The colonial regime draws its legitimacy from the use of force.”[2]

In April 2023, I published a book about the movement for migrant rights in France, which emerged through Palestine solidarity campaigns in the early 1970s. Natives Against Nativism: Antiracism and Indigenous Critique in Postcolonial France tracks the emergence of grassroots antiracist movements in solidarity with Palestinians and indigenous Americans, placing these movements on a colonial continuum that stretches back to France’s empire and across other Eurocolonial formations, notably Israel-Palestine and the US. At the heart of the book is the question of what continues to drive pro-Palestinian solidarity in France, more than a century after the beginning of colonial settlement in Palestine. My study of antiracist collectives and pro-Palestinian literary works and films from the past fifty years shows that Palestine reactivates anticolonial critique in a present we have too quickly dubbed postcolonial.

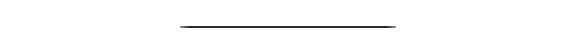

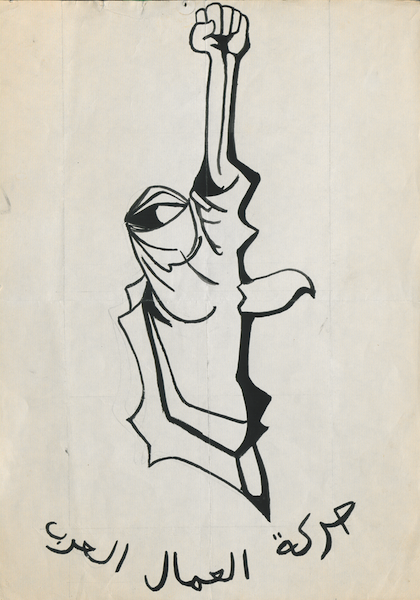

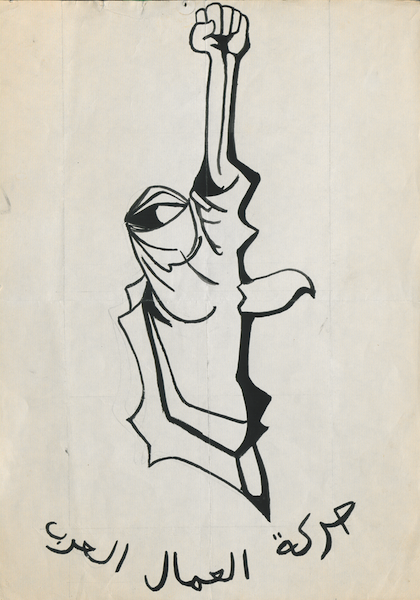

Figure 1. Logo of the Arab Workers’ Movement (1972-1976): a worker raises his fist in the shape of Palestine. Source: Fonds Saïd Bouziri, La contemporaine. Courtesy of Faouzia Bouziri.

Natives and Nativism is a book about antiracism and Palestine solidarity. What became clear to me in the aftermath of October 7 is that it’s also a book about the history of the suppression of pro-Palestinian speech. The past six months have seen an acceleration in the harassment, silencing, and physical violence against pro-Palestinian and Palestinian activists. I’m thinking of attempts to cancel cultural events, like Adania Shibli’s award ceremony at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the doxing of pro-Palestinian activists in the US, the ban on pro-Palestinian protests in France, Germany, and Vietnam, and more gravely still the murder and maiming of Palestinians in the US, including children. To be Palestinian or pro-Palestinian outside of Palestine-Israel is to risk severe legal consequences, including death and deportation.[3]

I’ll mention a French case that shows to what extent the suppression of pro-Palestinian speech is intimately tied to the suppression of migrant rights. On October 16, 2023, undercover French police arrested Gazan feminist activist Mariam Abu Daqqa in Marseille, following an Interior Ministry expulsion order that claimed that her presence on French territory after the Hamas attacks of October 7 was a threat to “public order.” A member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Abu Daqqa was arrested one week after the October 7 attacks and one day after an Islamist Russian national murdered a French schoolteacher, Dominique Bernard, in Arras. Despite legal attempts to stay the deportation order, she was deported to Cairo on November 10. In the following weeks, the Abu Daqqa and Bernard cases were instrumentalized to support a proposed law that would make it possible to deport immigrants displaying “behavior not compatible with French values.”[4] Abu Daqqa is a feminist activist, which is presumably compatible with the values of the French Republic, and it helps that she does not wear the veil. But in the context of France’s ongoing war on terror, what this means is that to be Palestinian or pro-Palestinian is to be a potential terrorist.

It’s crucial to insist on the decades-long history of Palestine solidarity in France because Palestine has become a reverse litmus test for French identity: if you’re pro-Palestinian, you’re not really French. The foreignization of Palestine solidarity is part and parcel of the foreignization of racialized subjects in France since the 1970s, which marked the emergence of the nativist anti-immigrant right, and the invention of the figure of the migrant as a guest whom we should either welcome with open arms or send back to his or her country of origin, regardless of the risks he or she might face. The figure of the migrant as guest is based on the erasure of the intertwined histories that produced migration on a mass scale, histories that begin with Eurocolonial expansion and include the ongoing colonization of Palestine. And yet despite these attempts to dehistoricize the figure of the migrant, Palestine continues to remind us of the colonial genealogies of migration, as it did in 1970s France. This, I suspect, is one of the reasons Palestine solidarity represents a threat to “public order” in France: it is a threat to the neat division between French citizens and France’s former colonial subjects. To recognize Palestinian rights would mean recognizing migrant rights: the political right to equality within a truly decolonized state.

[1] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 183; translation modified.

[2] Ibid., 5; 42; translation modified.

[3] One of Trump’s promises if he is reelected is that pro-Palestinian immigrants will be deported. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/11/us/politics/trump-2025-immigration-agenda.html

[4] The January 26, 2024 immigration law includes several articles specifying measures to deport “foreigners who represent a grave threat to public order.” See for example article 46: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000049040245.

Olivia C. Harrison is Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. Her research focuses on postcolonial North African, Middle Eastern, and French literature and film, with a particular emphasis on transcolonial affiliations between writers and intellectuals from the Global South. Her publications include Natives against Nativism: Antiracism and Indigenous Critique in Postcolonial France (University of Minnesota Press, 2023), Transcolonial Maghreb: Imagining Palestine in the Era of Decolonization (Stanford University Press, 2016), and essays on Maghrebi literature, Beur and banlieue cultural production, and postcolonial theory. With Teresa Villa-Ignacio, she is the editor of Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics (Stanford University Press, 2016) and translator of Hocine Tandjaoui’s proem, Clamor/Clameur (Litmus Press, 2021). She is currently working on a book project titled The White Minority, which tracks the settler colonial genealogies of nativism and anti-immigrant discourse in France.

Litmus Press’s programming is defiantly anti-border, anti-war, anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial. We as an organization do not work with, support, or accept support from the Israeli government, and we commit to continued solidarity with the people of Palestine.