COVID Reading: States of Confinement in Danielle Collobert’s It Then

With the last gasp of summer behind us, the outlook for winter 2021 is grim. As COVID cases surge, states are imposing new restrictions on interactions in public and private spaces. The isolation necessitated by the virus was difficult enough during the first wave; now, after having experienced the exhilaration that came with the bit of freedom afforded by warmer weather, this next round of semi-quarantine may prove to be an even greater emotional trial.

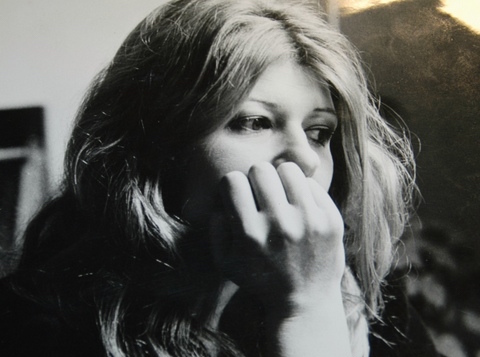

Turning to artworks that grapple with isolation, and—through the deep acknowledgement entailed by aesthetic encounter—come out, somehow, on the other side of it, seems like the thing to do at this moment. It Then by Danielle Collobert, published by O Books in 1989, is a book of poems tracing a struggle to articulate the strange disembodiment of seclusion; the elusiveness of self when there’s a scarcity of others to reflect, assure, and validate one’s own being. This work reflects the rhythms of Collobert’s life, which oscillated between intensely collaborative activism and deep isolation, as she was an active member of the Algerian liberation movement during the Algerian war, which later drove her into exile in Italy.

As an exile and first-hand witness to political violence, Collobert’s writing often evokes scenes of torture. It Then articulates a pain inflicted by an unnamed source: it could be the self, a human agent, an environmental agent, or some combination of those—

body striking – disfiguring its limbs with the too full pain – which body sudden empty – which violence against – about empty – pain congealed at last – wanting to reach it to set it once and for all – to keep it there motionless – or set it down in front of it – itself – to make it really visible – in its infinitely numerous images – unceasingly a body there – no – that body there – the one banging its face against the wall – maybe – no (18)

In her essay “‘Slammed into Walls’: Violence and the Impersonalized Subject in Danielle Collobert’s It Then,” Francis Kruk examines Collobert’s poetics, observing that “one of the chief sources of the violence in the text is the fact of not knowing, of facing an ambiguity” (119)—

sometimes slips out – separates itself – solidified – a word – walled up inside – doesn’t slip out – it cries out – yells – always the same word – twists – chokes without expulsion – neither spit – nor vomit – slow burning – fulminating (28)

This is the fretful vigilance of an isolated mind both accustomed to its isolation and keyed to the sporadic, sometimes violent intrusion of hostile external elements. Such a state induces a hesitant, protective relation to words:

We do not know what this word is, or in whom it is “walled up.” We do not know if “it” is walled up or even if it manages to “expel” that word in a manner comprehensible by the other voices. “It” might be a prisoner refusing to speak that word; “it” might be that person’s tormenter. (119)

And yet, this distressed language hints at a vision of impending release:

By facing that void and carrying out a painful écriture, Collobert creates an indefinable speaking subject that is able to “dream up a place where identity happens” (113), and to transcend the language we know, entering one where the impersonal “it” can truly revel in its abandon. (127)

Ultimately, Kruk finds in the writing’s impersonality a striving for transcendence. The possibility of experimental identity-formation is a motivating promise arising from the wreckage of a shattered self. Even with the misery of isolation and the anxiety of not knowing what’s coming, the self-emptying that is caused by these conditions also suggests the energizing possibility of creative re-constitution: of new forms, new selves, and new systems.

This transcendence through poetic transformation is likewise what Leigh Jajuga finds most powerful in the work:

Danielle Collobert’s It Then is something I return to as therapy, as heartbreaking consolation, a work that reminds me to rearrange my body. Perhaps to tell my body I am not body, but language, if not breath. In a state of anxiety, everything separates, rejoices in deconstruction, how to make sense of what the body is not. In Collobert’s It Then, I imagine duration, that the ability of ourselves to transmutate is survival—how we find our ability to endure.

Following Collobert’s cues, we might use this time to attend privately and creatively to our deepest selves, to rearrange ourselves, and thus prepare to collectively make a radically different future.