Feminist Bookstore News & The Post-Apollo Press

Part I: All the News…

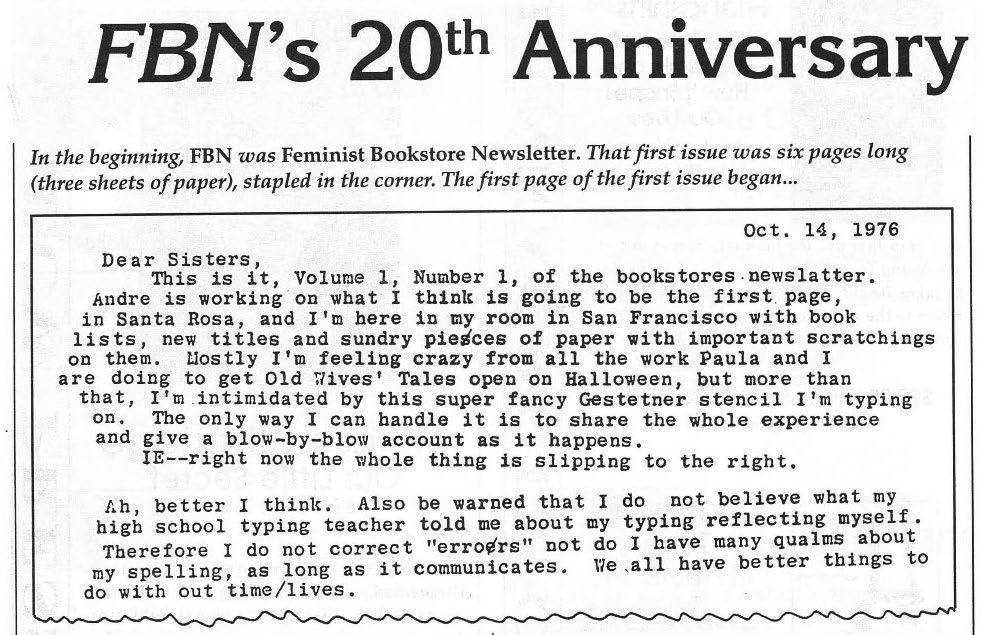

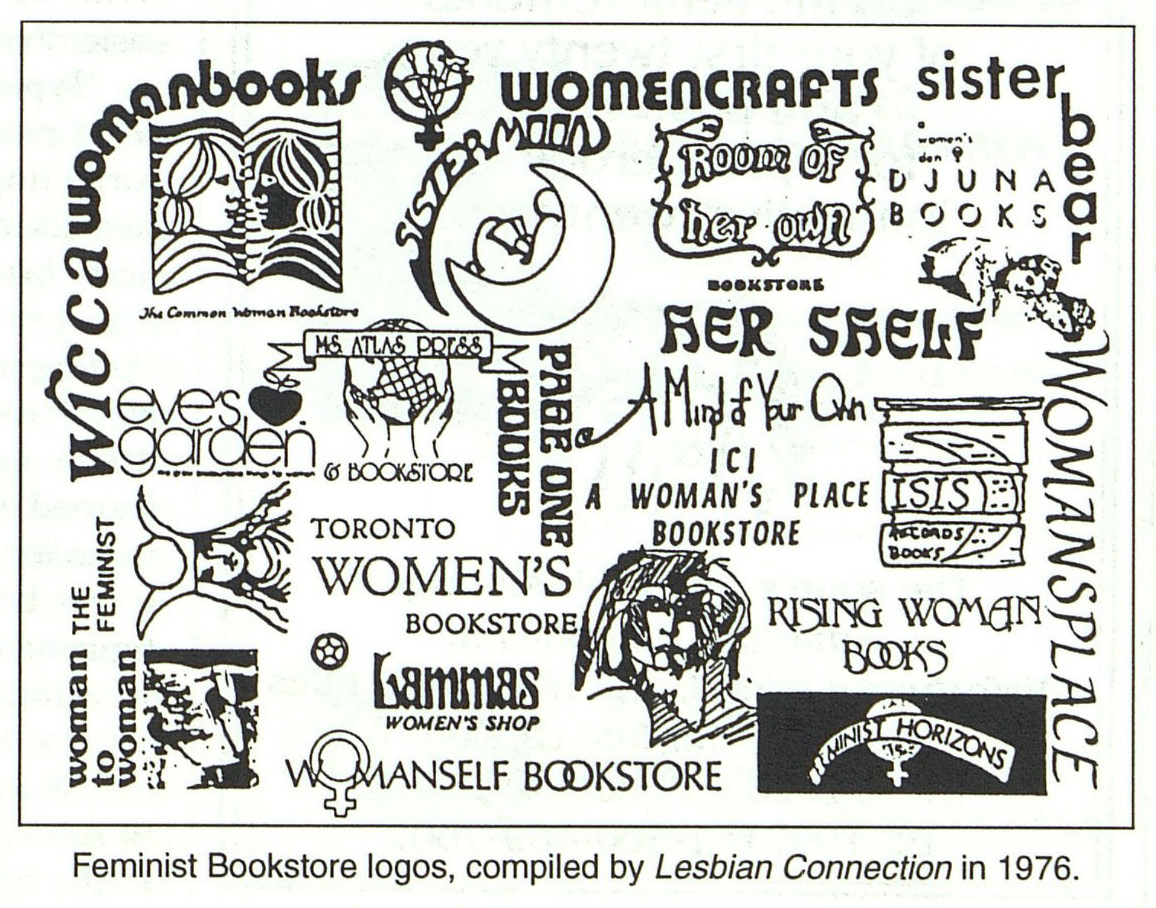

It arrived between four and six times a year, a 7-by-8.5-inch, saddle-stitched booklet with colored card stock covers printed in black ink, holding anywhere between 50 and 150 pages of feminist & queer nerd heaven. Feminist Bookstore News, a trade publication intended for book sellers, librarians, and college instructors, was a journal by and for book workers—those unsung laborers whose devotion to writing really puts it into circulation. Feminist Bookstore News was founded in 1976 by activist lesbian bookseller Carol Seajay (co-founder of the San Francisco bookstore Old Wives’ Tales) following the first National Women in Print Conference. The first issue of FBN was a three-page folded and stapled pamphlet that Seajay intended as a means of keeping conference participants in touch with each other. Something clicked, and FBN continued to run with Seajay as publisher and editor-in-chief for an impressive 24 years—ceasing publication with volume 22, issue 6, in summer 2000.

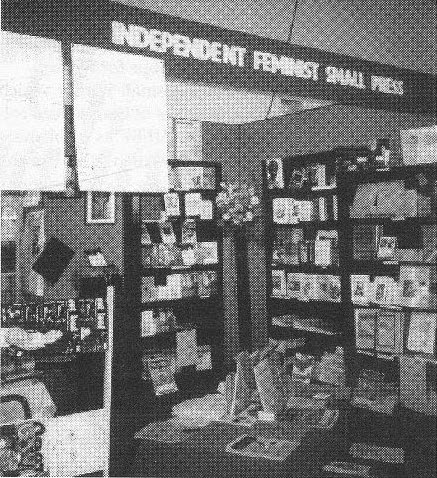

Image gallery 1: Assorted covers from Feminist Bookstore News throughout the years.

FBN‘s Electric Archive

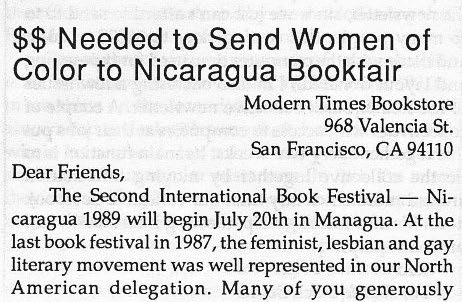

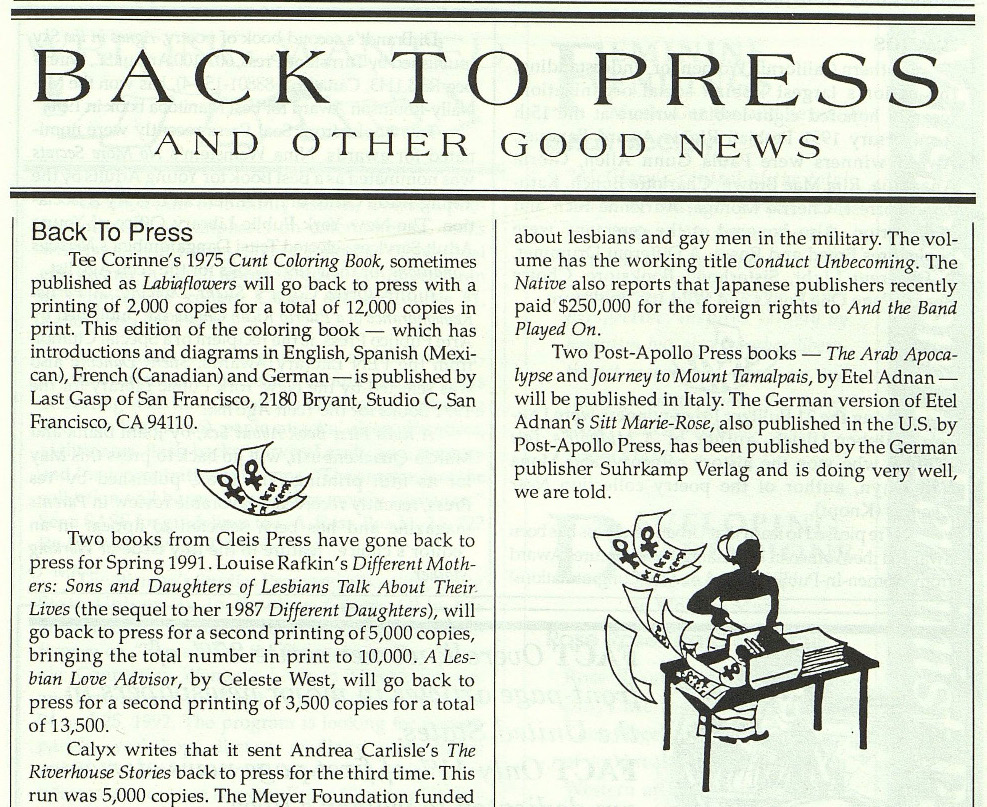

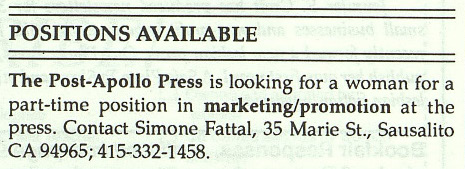

I first encountered Feminist Bookstore News when researching press clippings for titles published by The Post-Apollo Press. It was fall 2020 and we at Litmus were in the thick of building our new website, which would bring together Litmus Press’s catalogue with those of The Post-Apollo Press and O Books—two now-historic feminist presses whose back lists we manage and distribute. I don’t recall what I first ran across. Perhaps it was an ad for Georgina Kleege’s Home for the Summer, or a short review of Etel Adnan’s Journey to Mount Tamalpais—or was it this 1992 FBN classifieds listing that felt at once old-fashioned and radical in its gender-specific call: “The Post-Apollo Press is looking for a woman for a part-time position in marketing/promotion.” I can’t say for sure, but whatever it was that first caught my attention, it led me into a deep trove of open-access, digitized print matter—including the near-complete run of Feminist Bookstore News—hosted on JSTOR as part of the Independent Voices collection. Within this collection are 93 scanned and searchable issues of FBN, starting with volume 7, issue 1 from 1983 and ending with the final issue in 2000. The Post-Apollo Press appeared in a quarter of these issues—in advertisements, book reviews, and elsewhere.

Image gallery 2: Advertisements for Post-Apollo books and a classifieds ad for an open position at The Post-Apollo Press.

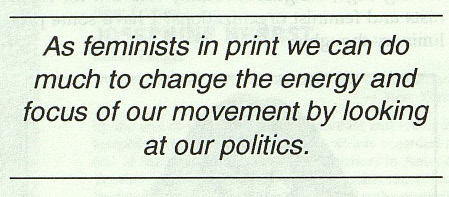

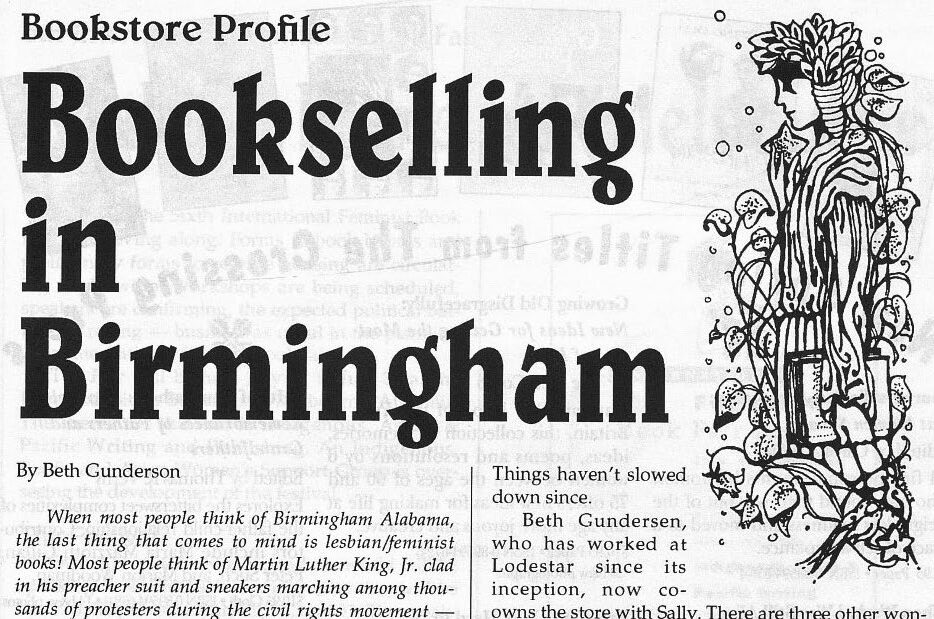

Just what was Feminist Bookstore News? Well, for starters, in each issue, reviews of hundreds of books of all genres from feminist presses based in the U.S. and abroad. Censorship and banned books news. A “Back to Press” section featuring back-in-print titles, and “They Went That-a-Way,” a column with practical updates about bookstore closures, openings, and relocations. Themed issues on topics like addiction and recovery, women & travel, university presses, little magazines, humor, kids’ books, and more. A dedicated section on “Gay Men’s Lit for Feminist Bookstores” and another for “Canadian Content.” Reading lists, trivia, a classifieds section, letters to the editor, interviews, publisher and bookseller spotlights. Articles on issues relevant to the book industry—from recycled paper availability to workplace sexism and sexual harassment. Obituaries for feminist booksellers and writers. Advertising for hundreds of feminist bookstores, presses, and magazines. Feminist comics and illustrations… A better question might be: What wasn’t Feminist Bookstore News?

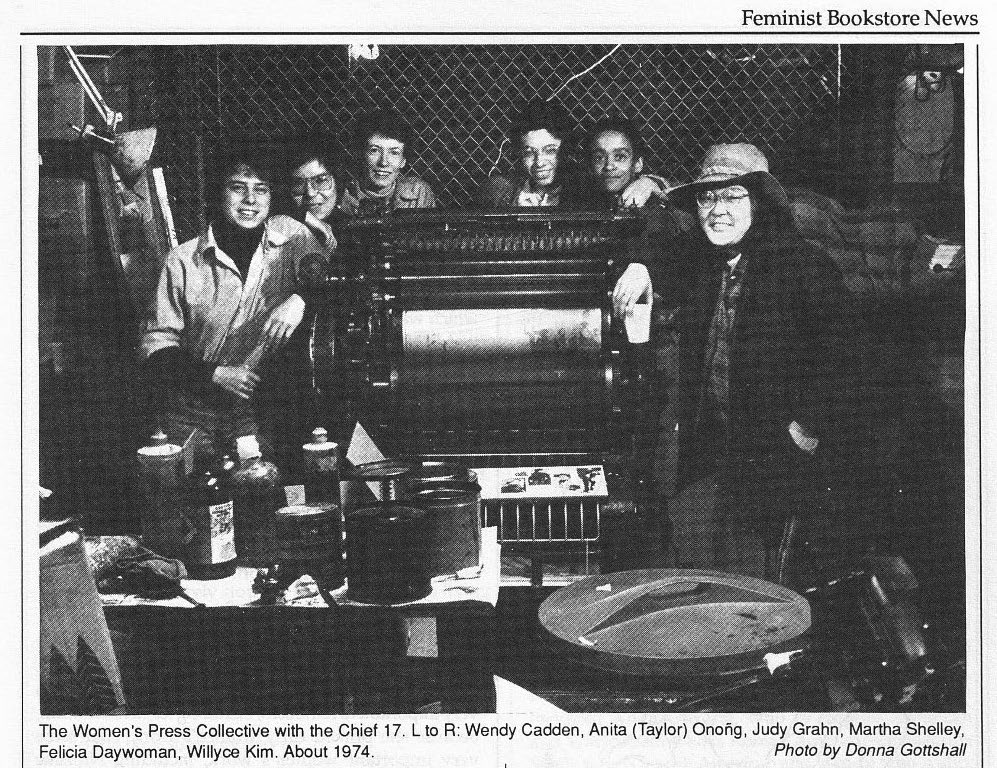

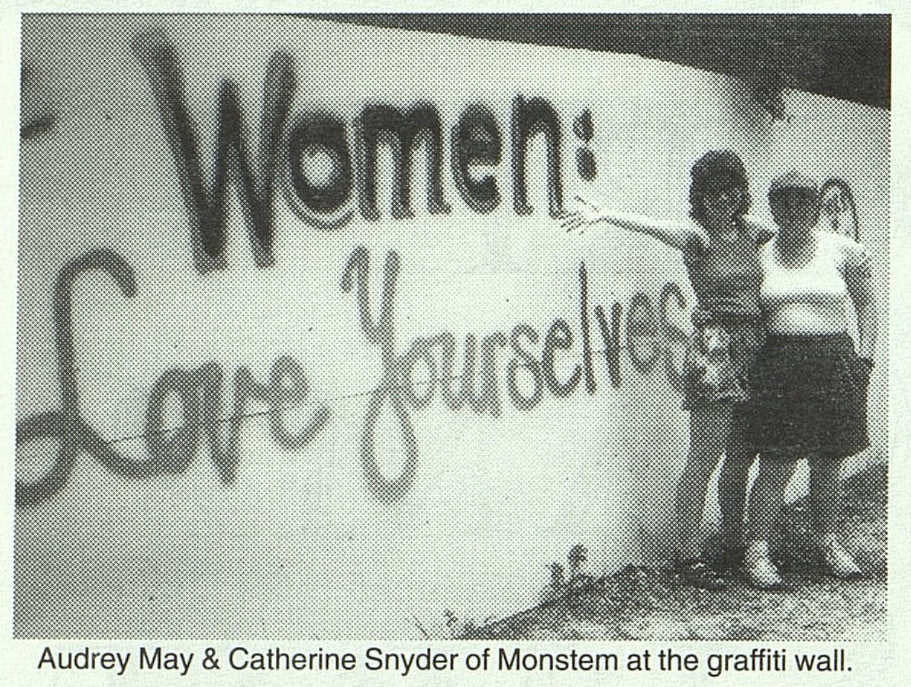

Image gallery 3: Assorted graphics, columns, and headlines from Feminist Bookstore News through the years.

Part 2: Boosting Feminist Networks & Culture

According to the descriptive summary of FBN’s archives, held at the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center of the San Francisco Public Library, “FBN was widely considered the Publishers Weekly for the feminist book trade, with book news, business news, inspirational features, and a forum for sharing the problems faced by and the successful strategies employed by other publishers and bookstores.” As FBN put it in their statement of purpose (appearing in the annotated bibliography Feminist Periodicals): “FBN is the communications vehicle for the informal network of feminist bookstores. Every issue contains articles on bookstore policy and politics, as well as over 200 book reviews and announcements. Also read (with a passion) by feminist librarians and women’s studies instructors.”

Within its pages, the evidence is abundant: FBN brought a concentrated visibility to these “informal networks” of feminist publishers and booksellers. In so doing, it strengthened them—facilitating further dialogue and collaboration among the co-creators of this decidedly un-monolithic counterculture.

The Post-Apollo Press in the Pages of FBN

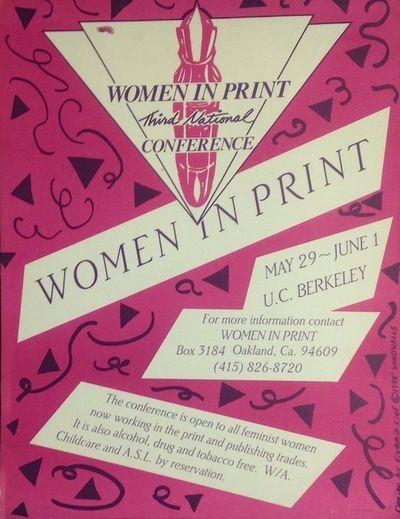

Taking The Post-Apollo Press as a sort of case study, we see that the press used Feminist Bookstore News as a conduit for announcing new books, posting job openings, etc. But we also find other less-expected manifestations of the work of the press and its publisher, Simone Fattal, recorded in the pages of FBN. For example, we encounter Fattal as a signatory on the 1985 Women in Print Publishers Accords, which were published in volume 8, issue 2/3 of the same year. Drafted by four representatives of three presses (Aunt Lute, Spinsters Ink, and Acacia Books) at the 1985 Women in Print Conference, these accords set out a “statement of responsibilities” for feminist publishers. They were later signed at the conference by eight more individuals representing six presses, including Simone Fattal of The Post-Apollo Press.

The accords begin:

As publishers of feminist and lesbian feminist literature we wish to acknowledge that we will abide by the following statement of our responsibilities:

1) We believe our responsibilities should be first dictated by our individual and collective political commitments and only secondarily by our business requirements. We also acknowledge the differences and diversity of our political commitments and urge readers and writers to acknowledge these differences…

Continuing for two pages, to item 4E, the accords detail publishers’ responsibilities to their authors, especially with regard to book contracts, licensing, and marketing.

Poster for the Third National Women in Print Conference, held at the University of California, Berkeley from May 29 to June 1, 1985.

In the November/December 1992 issue of FBN, Simone Fattal and The Post-Apollo Press appear in another notable context—this time listed as a member of the newly formed “Library Project.” “The Library Project” (later called the “Women’s Presses Library Project” (WPLP)) was created by a group of eighteen feminist presses who “joined forces,” FBN informs, “to address the exclusion of feminist presses by library jobbers and to expand the presses’ working relationship with the ALA [American Library Association] Feminist Task Force.” Following this description of the group’s mission, FBN gives an account of the Library Project’s specific action items and membership dues structure, as well as the names of participating presses and the group’s contact information, for other feminist presses wishing to join.

What further involvement The Post-Apollo Press had in the Library Project is not known to us through the pages of FBN, but we do find the press represented on the WPLP website for as long as the group continued to operate. WPLP discontinued its work in 2001, just a year after the last issue of FBN circulated. WPLP had a decade-long run of building relationships with the ALA Feminist Task Force and other ALA groups, as well as individual libraries and librarians. According to their website (which was maintained until 2002 and is now incompletely indexed by the Wayback Machine), in 1998, the WPLP represented 30 presses and close to 400 titles in 80+ subject areas.

Part 3: “Invasion of the Chains”

The near-simultaneous conclusion of the activities of FBN and WPLP is no coincidence. In Kristen Hogan’s The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability (Duke UP, 2016), Hogan charts the rise of North American feminist bookstore networks and culture from the 1970s to the early 21st century, when the majority of feminist bookstores shuttered due to rapidly changing economic and material conditions of book production, distribution, and consumption—including the emergence of e-commerce sites like Amazon.com and the “illegal and damaging practices of chain bookstores in connection with big publishing” (xviii).

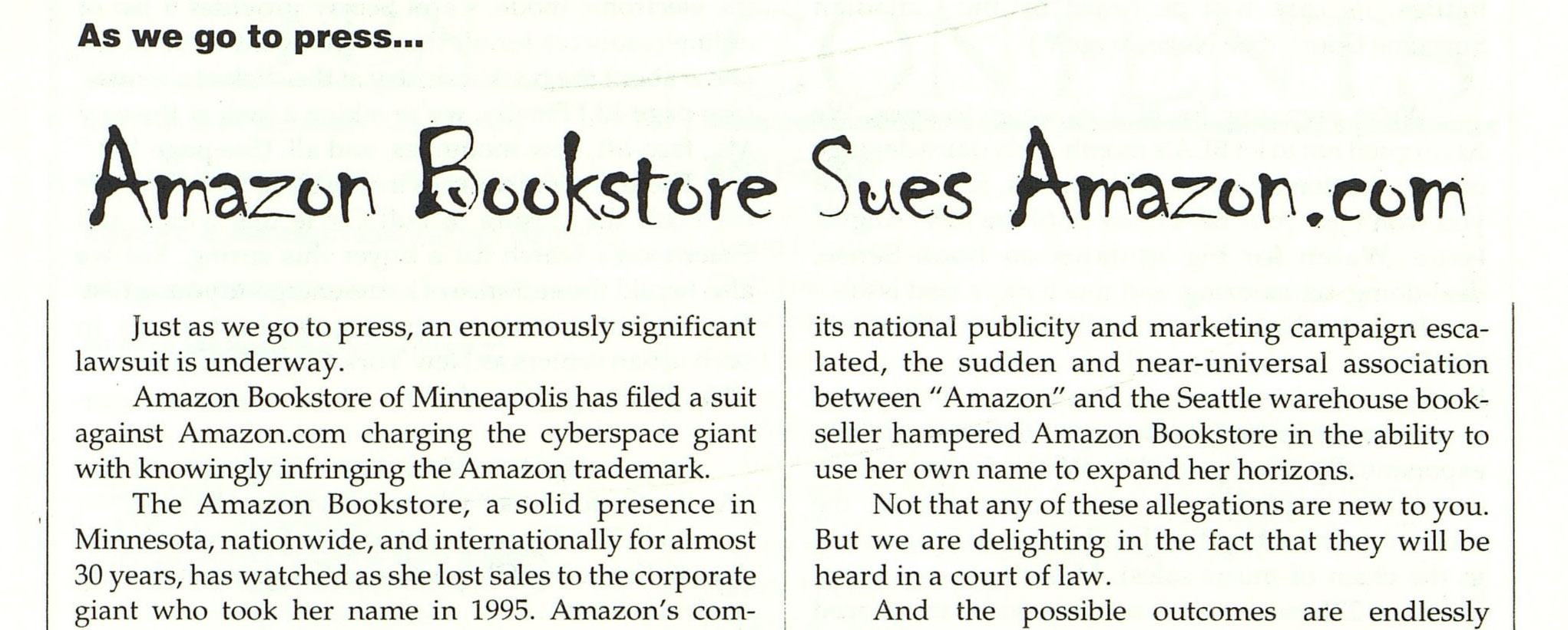

In a review of The Feminist Bookstore Movement, John Swab focuses on a section of the book that appears at least symbolically key to the story of the decline and disappearance of feminist bookstores at the turn of the millennium. This section caught my attention, too, as it deals with a 1999 lawsuit between the one of the first feminist bookstores in the U.S., Amazon Bookstore Cooperative (known as Amazon), which opened in Minneapolis in 1970, and the soon-to-be retail giant Amazon.com, which first established itself as an online bookseller in 1994/95. As the e-commerce site ballooned in the late ’90s, Amazon brought a lawsuit against Amazon.com for trademark infringement. Representatives of Amazon argued that the duplicative name was causing confusion among book buyers and vendors and was negatively impacting the feminist bookstore’s sales and work.

In the process of this lawsuit, Jeff Bezos’ lawyers resorted to lesbian-baiting tactics, interrogating booksellers in court about their sexual orientation, and arguing that Amazon Bookstore’s line of business was not bookselling per se, but “promoting lesbian ideals in the community” (cited in Hogan, 170). In order to have a case for trademark infringement, Amazon had to argue that they were, in fact, in the same business as Amazon.com, even if their “business model” could not have differed more. Ultimately, Hogan argues that “The language required of the lawsuit against Amazon.com further reframed bookwomen’s work,” feeding into a “new professional identity [that] erased public memory of their [bookwomen’s] vibrant history of necessary movement-based activism” (174).

As Swab elaborates, the lawsuit had the effect of

…undermin[ing] the work of the feminist bookstore, categorizing it as just another bookseller and not a place for community development and social justice-driven work. In the end, Amazon settled with Amazon.com, paving the way for the warped publishing and bookstore environment of today. At their height in the 1980s, there were more than 130 feminist bookstores across North America. Today, only 12 remain.* (4)

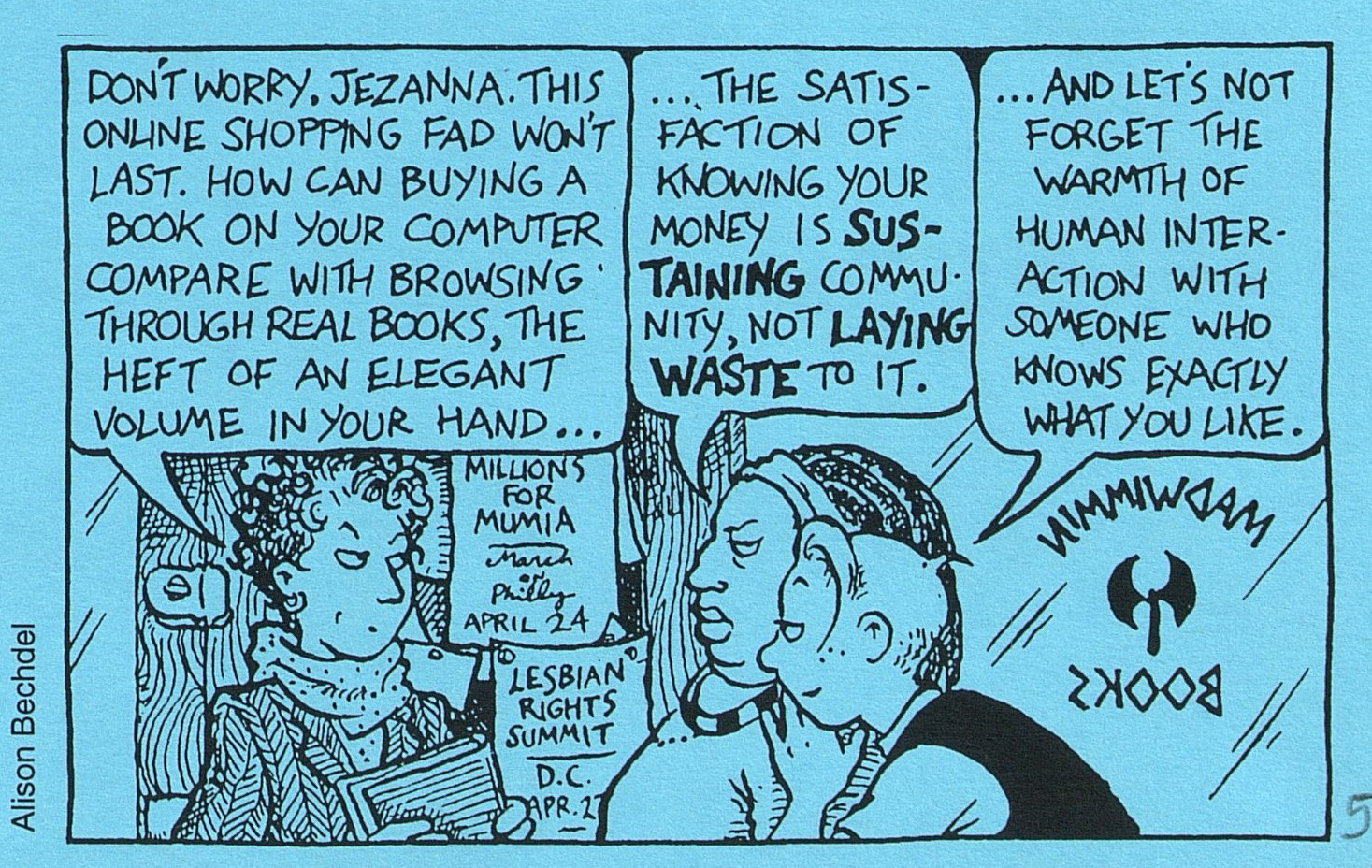

While it is perversely poetic to see, in retrospect, Amazon.com making an appearance at the very inception of the anti-feminist, corporate tide that would decimate so many vital community spaces and networks, the Amazon-vs-Amazon.com clash is emblematic of only one piece of a larger and more complex convergence of political-economic and social-technological forces that led to the undermining of feminist bookstore spaces and their networks of art, activism, and community. Anxieties about these myriad changes, and the struggle to adapt and survive, were freely and frequently expressed in the pages of FBN.

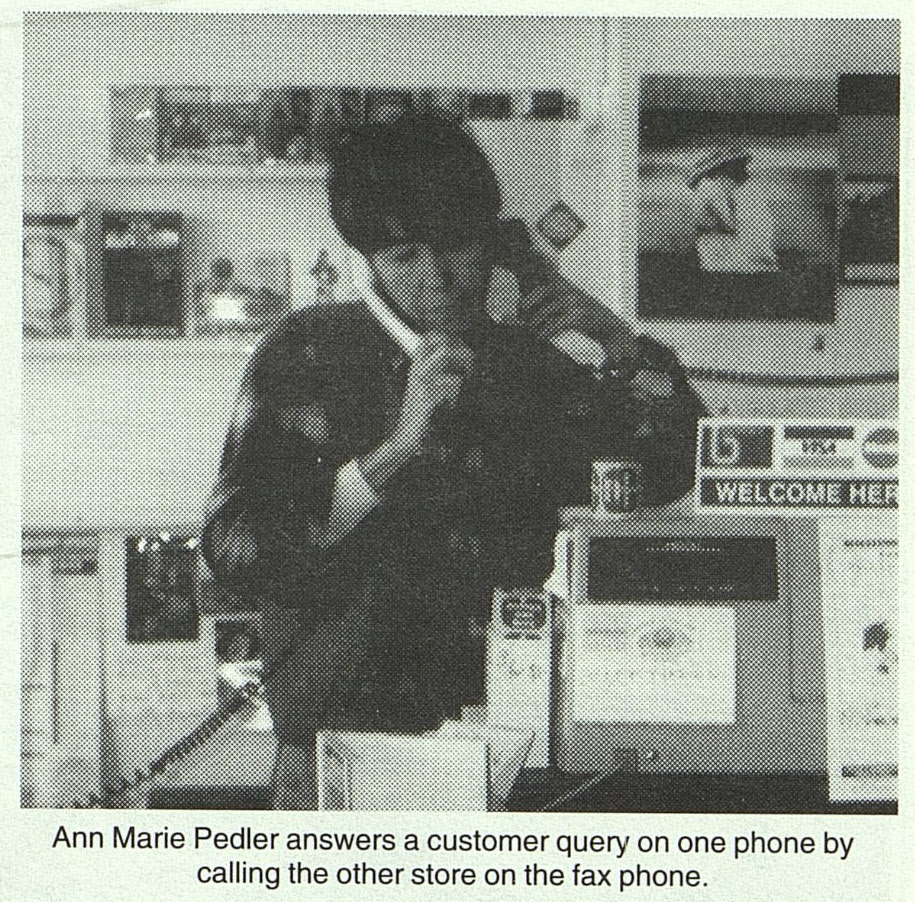

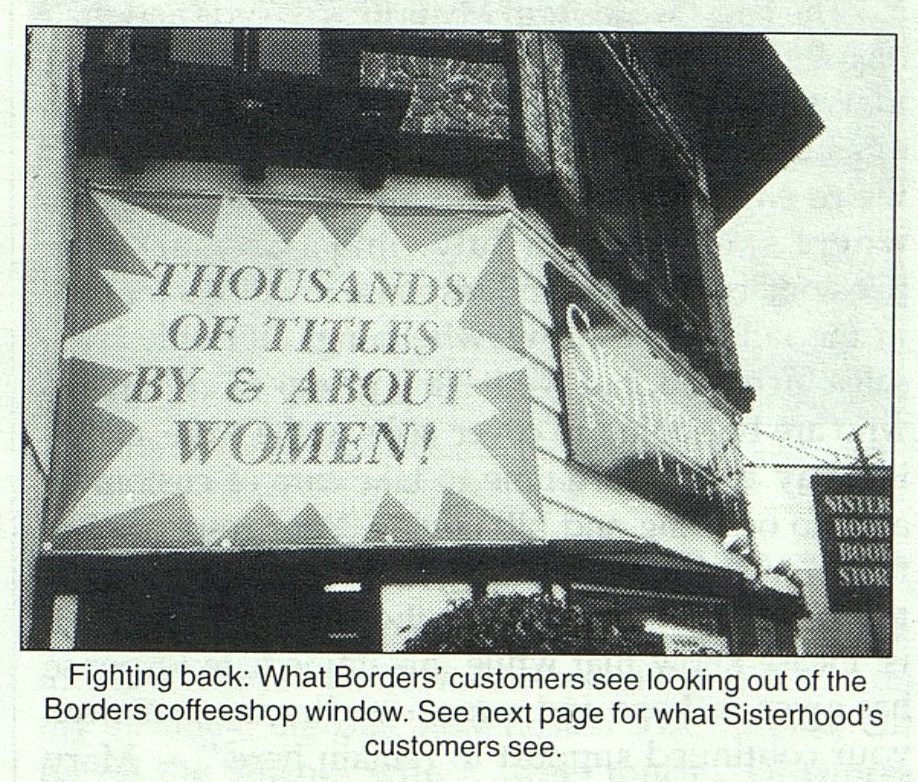

Image gallery 4: FBN content from the late 90s focused on new technologies in publishing, and the threat of monopoly business and online retail to the existence of feminist bookstores. Notably, in the May/June 1999 issue, FBN reported a countersuit of Amazon Bookstore against Amazon.com.

The mission statement of the Women’s Presses Library Project’s was “Keeping Women’s Words in Circulation.” In the optimistic morning of the internet, it must have seemed that new technologies would help to advance such a mission—through instantaneous connection to “world wide,” mass (and niche), online communities via listservs, bulletin boards, email, chats, websites, and the like. In 1999, even as the WPLP was losing members and scaling back its work, the group framed these changes as a refocusing of energy toward the creation of “a comprehensive bibliography of women’s titles on its website” with a “searchable database by subject.” By 2002, WPLP Coordinator Mev Miller reported with regret that “for a number of reasons, this vision never became a reality.”

It is a now too-familiar irony that the promise of the internet to “connect” people may have had, at least in some cases, the opposite effect. As the internet radically reshaped publishing, changing the way people communicated, and giving rise to monopolistic tendencies in business, many print communities whose vitality derived from spaces of proximate gathering, began to suffer. With tidy, space-and-paper saving computers and the (relatively) cheap, (relatively) fast delivery speeds granted by a dial-up internet connection, one may have wondered: Who really needed a hundred-page trade journal landing in their mailbox four times a year? What was the point, when all this information could be disseminated “freely,” without printing and postage costs, and piecemeal, in an accelerated temporality, or, a more “timely” fashion? Like the WPLP, Feminist Bookstore News tried to make the transition online. As it turns out, print media, and the brick-and-mortar infrastructures supporting print, may have been critically necessary to the existence of these platforms.

Part 4: “into the outer reaches…”

For radical feminist networks, sites of physical gathering were (and, I would argue, still are) key to their functioning. Books and bookstores are not just artifacts and containers: They are sites of social presence and intimacy that solidify affective bonds and deepen investments into the work of their communities. Print networks, like those facilitated and amplified by FBN, served an important role as demonstrative materializations of feminist culture.

FBN was raised up out of the energy of a burgeoning radical feminist consciousness in the late twentieth century. It also fed into that energy and its cultural-political work. I keep returning to the irony of discovering (for myself) this incredible publication and the wider world it served and represented through a digital archive—the colorful covers of FBN arrayed on JSTOR like so many specimen in a boy’s butterfly collection.

But then again, it would be simplistic to blame technology for the end of FBN and the contraction of feminist bookstore networks across the U.S. The limitations and shortcomings of the internet are, in fact, our own. Nor does a new techno-dualism of the “physical” and the “digital” serve us any better than the older Cartesian split (on which it’s modeled) between an ego-mind and a mechanistic body. Feminist knowledge production—circulated on and off the page, in philosophy, theory, poetry, fiction, biography, and all those exciting refusals of genre that belong to feminist writing—has taught us at least this much. And that any living culture must continually make, unmake, and remake itself. Thus, the archive remains vital as a potential source of irruption and disruption. What, I wonder, in this moment, and on revisiting this archive, might we purposefully carry into our present in order to unmake and remake it?

— Rachael Guynn Wilson

Brooklyn, July 16, 2022

Image gallery 5: A diverse assortment of headlines, pull quotes, advertisements, features, special sections, and cartoons from Feminist Bookstore News.

NOTES

* I hope it’s already evident that such a precise number is subject to dispute. Hogan, for one, emphasizes that the authors of current lists of feminist bookstores “prioritize the bookstore [aspect] rather than the activism of feminist bookwomen.” This lens, she argues, causes them to overlook many vital bookstores operating through feminist politics and practices and to “obscure a more radical history of this movement” (xix).

WORKS CITED & FURTHER READING

“Feminist Bookstore News Records.” Online Archive of California. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qj7mpm/

“Feminist Bookstore News.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_Bookstore_News

Hogan, Kristen. The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Sullivan, Elizabeth. “Carol Seajay, Old Wives Tales and the Feminist Bookstore Network.” FoundSF. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Carol_Seajay,_Old_Wives_Tales_and_the_Feminist_Bookstore_Network

Stiefel, Emma. “Feminist bookstores: The legacy and lessons of a women-led movement.” San Francisco Chronicle. June 25,2022. https://www.sfchronicle.com/projects/2022/feminist-bookstores/

Swab, John. “Book Review Symposium: Queer Geographies.” Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography. May 14, 2016: 1-6. https://radicalantipode.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/14.-john-swab_ak.pdf